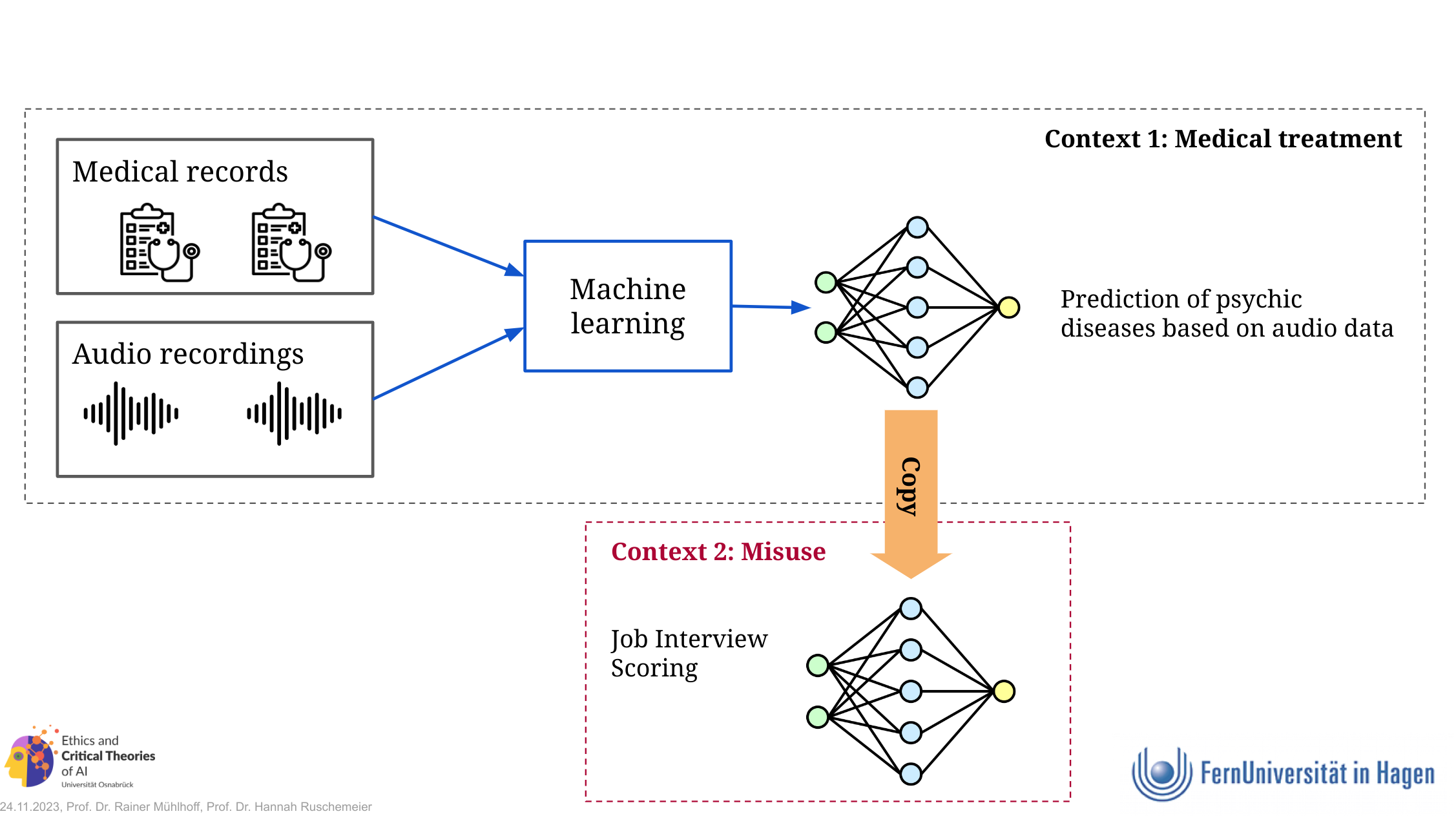

The Risk of Secondary Misuse of Trained Models

Imagine medical researchers developing an AI model to detect depression from speech data. The model is trained from the data of volunteer psychiatric patients, aiming to enhance medical diagnosis – a purpose that motivates many to consent to the use of their data. But what if the trained model is acquired by the insurance industry or a company that builds AI systems for job interview evaluations? In these cases, the model could enable implicit discrimination against an already vulnerable group.

Currently, no effective legal restrictions prevent the reuse of trained models for unintended purposes. This includes the GDPR and the AI Act. The secondary use of trained models poses a significant societal risk and presents a blind spot in ethical and legal debate of the potential societal impacts of AI.

Secondary Use of Training Data

Instead of transferring the trained model to an external party, the clinical research group could share the anonymized training dataset collected during their research. The external actor, for instance, an insurance company or provider of AI based hiring systems, could then use this dataset to train their own machine learning model to predict depression from voice data. Alternatively, the insurance company could also combine this specific training data with other data to train any other model from it.

If the insurance company utilizes the original training dataset that was collected by the research institution, or any model the company could train from this dataset, for insurance risk assessment, we regard this scenario as a secondary use of the training data. This secondary use surpasses and contradicts the original purpose for which the training data was collected by the research institution.

Why doesn’t the GDPR effectively protect against the risk of secondary misuse of trained AI models?

The GDPR does not apply to the processing of anonymous data. This means that the processing of both training data and model data, if anonymised (e.g., with differential privacy for machine learning), fall outside the scope of the GDPR. As a consequence, once a dataset is anonymised, the principle of purpose limitation is interrupted. This is particularly problematic because the GDPR privileges certain purposes, such as research and statistics, within the framework of purpose limitation: they are always considered compatible with the primary purpose of data collection. Additionally, the purpose limitation principle under the GDPR relies on the compatibility test of art. 6 (4) GDPR. However, the compatibility test does not apply when the secondary data processing is based on consent or a law of the Union or the member states.

Why doesn’t the AI Act protect against the risk of secondary use of trained AI models?

The provisions of the AI act apply only once an AI system is placed on the market. At that moment, every AI system is classified by the AI act according to its risk category. This classification relies on a dichotomy of product safety risks and fundamental rights risks. Crucially, the risk of secondary use of a trained model is not recognised as a risk factor in this classification, which either follows the categories of product safety law (art. 6 (1) AI Act) or the context based implications for fundamental rigths (art. 6 (2), e.g., biometrics, AI systems used in education or credit scoring). The secondary use of models therefore plays no role in the AI Act’s risk assessment framework.